With the release of Theatre Camp in cinemas, and Disney+ having just ended its longest-running show, High School Musical: The Musical: The Series (based on the beloved Disney film series), the current era of media is a haven for all those who were in their high school drama club. While the idea of a ‘theatre kid’ is understood by anyone whose school had an active drama department, its caricatures have been cemented in the cultural zeitgeist through their depiction on film and TV.

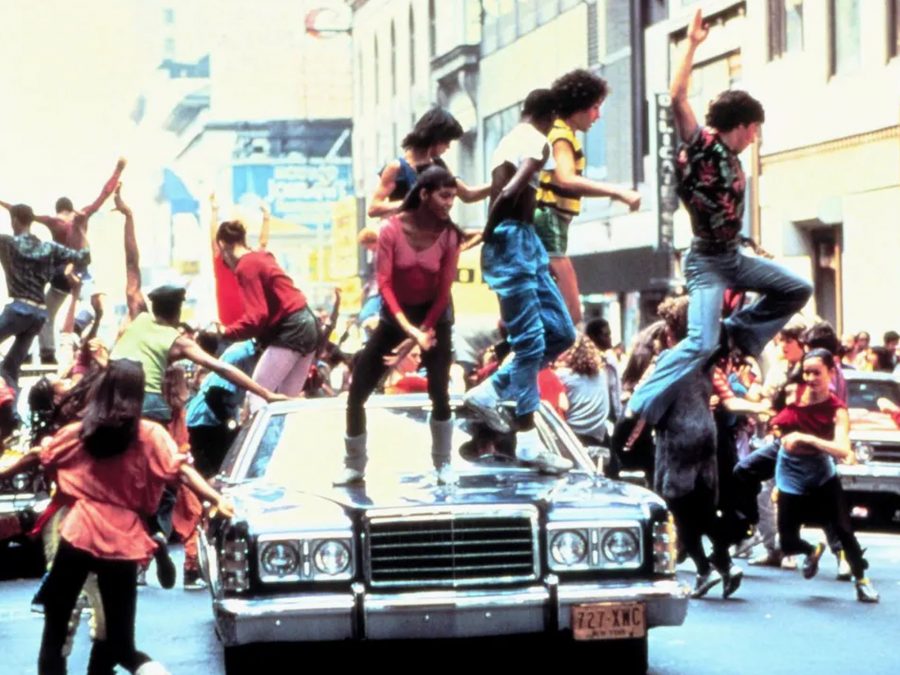

One of the seminal films about teens in the arts ironically feels set apart from much of what followed. Alan Parker’s 1980 musical Fame follows a group of students at a performing arts school in New York. It secured two Academy Awards for Best Original Song and Best Score, as well as critical recognition for Barry Miller’s performance as Ralph. It’s a gritty film that seeks to be authentic in its portrayal of teenage life, with Roger Ebert praising its “sensitivity to real lives of real people that we don’t get much in Hollywood productions anymore”.

Fame was unafraid to deal with dark subject matter such as suicidal thoughts, racism, and drug addiction – all of which should feel out of place in a musical, but somehow never do. While its ensemble cast and erratic pacing mean that you aren’t able to fully uncover the nuance of each student, what we see in them is determination and ambition to be something bigger than themselves, leaving a lasting legacy. We also see how the desperation to achieve this can lead to self-implosion. This is something that is true of all future depictions of drama kids, even if we are used to seeing a sanitised version more akin to the film’s TV spin-off and 2009 reboot than its original iteration.

Musicals are certainly the genre that most naturally leans to telling the stories of drama students, with integrated musical numbers flowing easily when they make narrative sense. Surprisingly, the film that helped to resurrect the form was Disney Channel’s High School Musical, which spawned a cultural legacy that remains today. It’s a simple boy meets girl story about finding your place in the world and breaking free from peer-imposed expectations. Its script is kitsch, but there’s something in the earnestness of it all that makes it a complete joy. Kenny Ortega (who previously choreographed Dirty Dancing and directed Hocus Pocus) caught lightning in a bottle with a cast led by an effortlessly charming Zac Efron and Vanessa Hudgens.

The already established theatre kids like Sharpay and Ryan (Ashley Tisdale and Lucas Grabeel) are camp and over the top, and the extent to which their lives depend on the success of their show is ridiculous. In contrast, Troy and Gabriella offer a softer, more subtle approach, as outsiders to the theatre department who still find an escape and home there, expanding the appeal of these narratives to those beyond the stereotype. It clearly had a universal appeal: its first sequel went on to score the highest viewership for a TV movie with 17 million viewers, and recognising the franchise’s popularity, Disney released the third High School Musical film in cinemas, where it grossed over $250 million at the box office. However, despite the strong nostalgia pull with adults today, High School Musical ultimately was aimed at children, and lacked an adult audience.

Fast forward three years, and Fox debuted its new musical series Glee. Still about theatrical high schoolers, and with a jock lead (Cory Monteith) who somehow gets pulled into the world, it marked a significant shift from High School Musical. It was marketed at teens and adults, with sex, cheating, teen pregnancy, and a wicked sense of humour. These days, the show is talked about as a bad fever dream, but the extent of Glee’s cultural impact is profound. It won Emmys and Golden Globes, staged an international concert tour, and its first single, a cover of Journey’s ‘Don’t Stop Believing’, reached number 2 on the UK charts. Where High School Musical thrives in its earnestness, Glee is defined by its self-awareness. Rachel Berry (Lea Michele) is an impossibly overexaggerated protagonist – remember that time she sent a competitor to a crack house? – and the show revels in exhausting every high school cliché. However, there is heart beneath the extremities, aided by a truly talented cast who could always get you to root for their characters in a meaningful way as they traverse growing up.

Glee paved the way for studios to believe in these comedies, and the success of Pitch Perfect in 2012 only cemented this further. Inspired by Mickey Rapkin’s book ‘Pitch Perfect: The Quest for Collegiate a Cappella Glory’, the three film franchise may focus on college students rather than high schoolers, but the camp theatricality and slight dissociation from reality remain. It again centres an outsider so as to widen its appeal – here it’s Anna Kendrick’s Beca – but in all of these musical depictions, the kinship and community that theatre kids have between them is crucial to understanding these characters.

Even outside musicals, theatre kids have made for compelling protagonists in teen narratives. Teen dramas historically have loved storylines where the cast put on a show, and in contemporary examples such as Riverdale and Euphoria, their usage has highlighted how theatricality can heighten the experiences of coming of age.

But even beloved auteurs Wes Anderson and Greta Gerwig had early breakout films (Rushmore and Lady Bird) that focused on theatre kids. Max in Rushmore (Jason Schwartzmann) and the titular role in Lady Bird (Saoirse Ronan), are defined by the neurosis that seems inherently linked to their theatricality. Like many who fulfil the trope, there is a self-importance that shapes their interactions with others, and a detachment from the things that truly matter. In the opening scene of Lady Bird, her mum yells at her, “you don’t think about anybody but yourself,” something that is also said in Fame by Mrs Sherwood to young, ambitious dancer Leroy. However, these theatre kids are still depicted as empathetic, feeling everything more deeply.

The balance of depicting neurotic tendencies and garnering empathy is a knack that Ben Platt (the archetypal theatre kid, whose father Marc Platt is a respected film and theatre producer) has mastered in Dear Evan Hansen and now again in Theatre Camp. It shows in his performance but also in his writing, as various reviewers have pointed to Theatre Camp as a film that is very much an in-joke between friends. Being both written by and starring theatre kids-turned-theatre adults (his friend Molly Gordon and fiancé Noah Galvin star) there is a hindsight that provides the satire, particularly regarding the unhealthy relationships between theatre kids and their teachers. But there is also a deep fondness for that world, meaning that the earnest tone captured in films like High School Musical can’t help but spill out, even in the mockumentary format.

In a review of the final season of High School Musical: The Musical: The Series, critic Fletcher Peters points to “satire and earnest stories of teenagers finding their true selves” as what the show does best. But this balance has been what cinematic depictions of theatre kids have always done best. What would be annoying in real life has an otherworldly charm on screen that when lovingly poked at, making for funny and empathetic storytelling that shows the tumultuous nature of growing up.

The post How theatre kids finally found their spotlight appeared first on Little White Lies.

from Little White Lies https://ift.tt/g4o0FKI

via IFTTT

0 Comments