Steven Spielberg has always been a director who has poured his heart and soul into the movies that he makes – this has never been more evident than in his latest film, The Fabelmans. For all intents and purposes, The Fabelmans could have been called The Spielbergs, as it is inspired by the director’s own life experiences and his passion for movie-making – a love affair that has spanned more than six decades and resulted in some of the greatest films of all time. Spielberg himself has said of The Fabelmans, “It wasn’t about metaphor, it was about memory.” This statement could easily apply to so many of Spielberg’s films – while his filmography is undoubtedly rich in meaning and symbolism, there has always been something of himself in his films as well.

Perhaps the most obvious example is what Spielberg’s films have to say about family – more specifically the idea of broken families and separation. The Fabelmans explicitly explores the fractures in the Fabelman family unit and the tumultuous relationship between parents Mitzi and Burt (played by Michelle Williams and Paul Dano respectively) – who are based on Spielberg’s mother and father, Leah Adler and Arnold Spielberg. Yet it is hard to ignore the recurring theme of family in Spielberg’s oeuvre – particularly during the ‘80s and ‘90s in films such as E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial and Hook. While quite rightly remembered as nostalgic childhood favourites, both films also explore the idea of absent parents and the effect this has on the children caught in the middle.

Elliott’s (Henry Thomas) father in E.T. is noticeably absent, and it is mentioned that he is in Mexico having recently left his family behind. This has a profound effect on Elliott – who you could argue is the stand-in for Spielberg in this film – and leads him to form a close connection with the alien he calls E.T. who has himself been separated from his family and is trying to make contact with them.

Spielberg credits his father with unlocking his fascination with the cosmos, stating in a 2005 interview that, “he led me to these wonderments of both nature and fiction.” Through films like E.T. and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Spielberg explores the pain of families torn apart against the vast backdrop of space – a constant source of wonder and inspiration for his movies, as well as one of the things he most closely associated with his estranged father.

The father perhaps most closely aligned with Spielberg’s own appears in Hook. Peter Banning (Robin Williams) is a workaholic father who may be physically present in his children’s lives but is far from being emotionally available to them, always putting work before them and missing out on important moments. While on the surface Hook is an imaginative retelling of J. M. Barrie’s classic Peter Pan, beneath that it is the story about a father having to fight for his kids, and making the conscious decision to show up for them.

Released in 1991, Hook came off the back of Spielberg’s own divorce in 1989, and in many ways, it can be seen as an expression of his commitment to fatherhood. In this film, Spielberg is not the children, he is Peter, and through this character we see him making a conscious decision to perhaps be the father that he felt he didn’t have following his parents’ divorce.

When Spielberg’s parents split, it had a huge impact on him and shaped the type of films he would go on to make. Art born out of conflict and pain is something that flows through The Fabelmans and can be seen throughout Spielberg’s movies as well. Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle) is warned by his mother’s uncle (Judd Hirsch) that his art will always be at odds with his family, and in a cruel twist, it is Sammy’s lens that captures the signs of his family breaking apart.

Just like Peter in Hook, Burt Fabelman is not an uncaring man, but one that frequently places work before family commitments. This drives the free-spirited Mitzi into the arms of Burt’s friend and business partner, Bennie (Seth Roger), and it is Sammy’s home movies that pick up on the warning signs that ultimately lead to the family being torn apart. Spielberg largely blamed the divorce on his father, and in the years following, their relationship was strained and distant – a pain that is woven through so many of his subsequent films.

There are some more overt examples of Spielberg working through his own feelings about his family’s circumstances – the separation of a boy from his family in the war drama Empire of the Sun being one that particularly focuses on the pain and trauma experienced when a family is torn apart. However, there are also some surprising angles where the director places himself in his father’s shoes to consider why someone would want to leave their family.

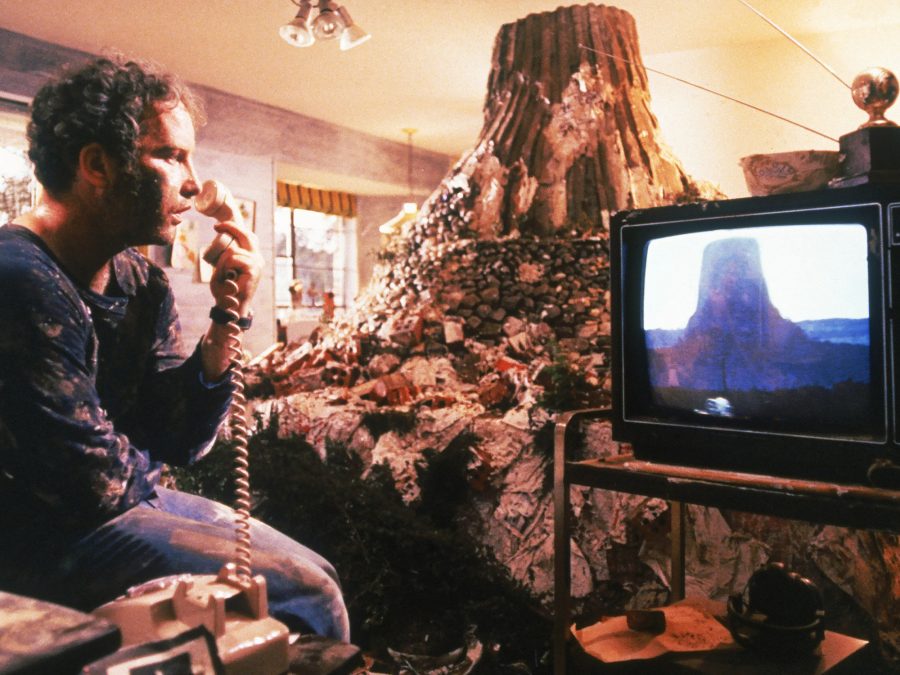

In Close Encounters of the Third Kind, one could argue that the character of Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss) is Spielberg’s attempt to try and see things through his father’s eyes, without going so far as to say that his actions were justified. At the end of the film, Roy makes the perhaps surprising decision to leave behind his family and go with the aliens. For him, this feels like the only choice he has – go and explore the beauty of the vast universe, or try to reconcile with his family who has made it abundantly clear they don’t support his alien obsession.

Spielberg admits that Close Encounters is not a film he would’ve been able to make after he became a father, saying to Variety, “It’s very easy to have somebody leave his family to get on a mothership when you’re not a father yourself.” While Spielberg isn’t trying to suggest that his own father made the decision to leave lightly, Close Encounters at least shows the director working through the reasoning of someone leaving – again against the backdrop of space that was so intrinsic to his relationship with his father.

Interestingly, The Fabelmans ties together some of the key themes of Close Encounters – technology and music – offering another compelling insight into the personal elements Spielberg likes to scatter through his films. Inspired by his own parents, Mitzi Fabelman is a pianist, and Burt Fabelman is a computer engineer. While their differences eventually lead to their separation, Close Encounters sees their elements brought together: technology, music, and science working together in beautiful, communicative harmony.

As well as the focus on families, The Fabelmans also sees Spielberg exploring the wistful romanticism of the movies – something that is particularly fitting given that he has been responsible for so many nostalgic film classics. For Sammy Fabelman, cinema is transformative, and it is Cecil B DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth that ignited his passion for making movies. Spielberg’s love of movies is evident throughout his career. The high-stakes thrills of Duel and Jaws took cues from the Master of Suspense Alfred Hitchcock, while his visual prowess and expert use of blocking were inspired by the sweeping grandiose filmmaking of John Ford – who memorably crops up in The Fabelmans played by David Lynch. Few directors seem to understand the craft of filmmaking and its rich history as well as Spielberg.

But what has become his trademark is that childlike sense of wonder at the endless possibilities of film. This is particularly evident in the Indiana Jones films. Working alongside George Lucas – a director who would share Spielberg’s giddiness for adventurous cinematic storytelling – these films evoke so many of the ones that Spielberg loves. Combining elements of 1939’s Gunga Din, movie serials like Flash Gordon, historical epics such as Lawrence of Arabia, the James Bond movies, Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns, and of course, John Ford, the original Indiana Jones trilogy in particular feels like films made by someone who loves movies with every fiber of their being. Crucially, Spielberg’s love of movies helps him to understand what makes a great one, and it is no wonder the films he directed have been so revered.

Rolling Stone has described The Fabelmans as, “the Steven Spielberg movie we’ve been waiting four decades for him to make.” While this is true in the sense that it feels like the synthesis of the story he has been telling in fragments for years, it fails to speak to the genius of the man who is so passionate about telling stories, so conscious of the impact they had on him, and so eager to use it as a means for growing and developing as a person, that almost his entire filmography feels biographical. It takes a true artist to turn pain into joy – particularly a joy that continues to speak to each new generation – and The Fabelmans is a testament to this. Movies can change the world. They changed Spielberg’s world, and now his movies have indelibly changed cinema history.

The post How The Fabelmans represents a culmination of Spielberg’s cinematic interests appeared first on Little White Lies.

from Little White Lies https://ift.tt/ryAPEet

via IFTTT

0 Comments