This year, two films have renegotiated the terms between observers and observed in noir-tinged narratives, exploring the fight for female agency. Chloe Okuno’s Watcher is a tight thriller about a woman stalked by a man living across the street, a story that continuously challenges the relationship between subject and object. Park Chan-wook’s Decision To Leave operates on a similar level, with a male detective and a female murder suspect playing a game of cat and mouse.

Both Julia (Maika Monroe) and Seo-rae (Tang Wei) navigate a foreign, sometimes hostile environment. An American who has relocated to Romania with her husband Francis (Karl Glusman) and a recently widowed Chinese carer in Busan, these women’s otherness exerts a magnetic fascination on locals. New iterations of the femme fatale archetype, they manage to elude the role’s most problematic implications and find strength in their gaze.

With the police and Francis doubting her sanity, a terrified, alienated Julia cruises Bucharest’s underbelly, following the man who’s been leering at her. Seo-rae’s descending trajectory may serve the male protagonist to an extent, but also reveals a woman who carefully doses how much of herself she’s willing to give to Hae-jun (Park Hae-il). Aware the cop is tailing her to determine whether she killed her abusive husband, Seo-rae uses this knowledge — and a perfectly timed code-mixing of Chinese and Korean — to stay one step ahead and spy on him instead.

These two examples of female agency are dramatically different from those of the 1940s and 1950s noir. While these classics of the gebre have the merit of having expanded the pool of roles for actresses, they would still feature characters inscribed within a male-centered narrative. This is apparent in the way the camera framed this supposedly deadly woman, either introduced by zooming in on her figure (Orson Welles’ The Lady from Shangai) or through a series of voyeuristic details (Hitchcock’s Vertigo), underlining she’s a sight to behold before anything else.

Fast forward several decades and the neo-noir genre now allows female leads to emerge in a new light. Not long after Laura Mulvey applied the male gaze theory to film criticism, there have been attempts to flip the script, reevaluating the visual relationship between women and men.

However, the reaction to 1983’s indie noir Variety proved the new language to critique female stories hadn’t stuck quite yet. Bette Gordon’s movie was dubbed “a feminist Vertigo” by LA Weekly, reducing its radical aura in an easy comparison with a male-focused movie.

A noir in its own right, Variety follows aspiring writer Christine (Sandy McLeod). A cashier at an adult cinema in Times Square, she becomes involved with distinguished patron Louie (Richard M. Davidson), who may have ties with the local mob.

The camera lingers on the protagonist watching Louie from afar, subsequently giving this homme fatale the compartmentalising treatment normally reserved for women’s bodies, broken into chunks to maximise male gratification. Gordon’s film includes a montage of Louie’s hand shaking those of various business associates, materialising Christine’s increasing fixation. Meanwhile, she revels in this attraction, projecting her fantasies onto the cinema screen to awaken her sexuality and get her creative juices flowing.

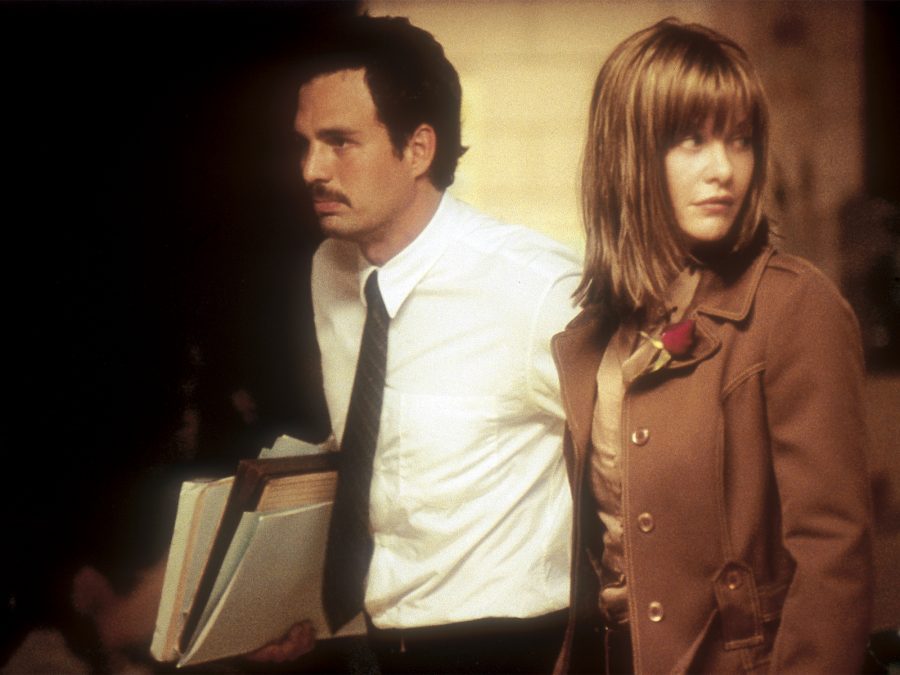

A similarly dismissed neo-noir, Jane Campion’s In the Cut is a compelling portrayal of burgeoning female sexuality. The adaptation of Susanna Moore’s novel sees Meg Ryan playing against type, trading her America’s sweetheart persona for a less likeable role. An uptight English teacher living in New York City, Ryan’s Frannie gets entangled in a heinous murder with no-nonsense detective Malloy (Mark Ruffalo), whom she suspects may be behind it.

Frannie’s sexual renaissance occurs through visual perceptions first and foremost. In one of the movie’s most shocking scenes, the protagonist spots a woman giving a blowjob to a mystery man in the back of a bar and stands there, mesmerised. Later on, she’s captivated by Malloy’s matter-of-fact demeanour, studying his every move in the streets as she does in the bedroom.

But it’s another sequence that indicates a change in Frannie, whose resistance to eye contact suddenly switches. In the back of Malloy’s patrol car, she holds his partner Rodriguez’s (Nick Damici) gaze in the rearview mirror as he’s questioning her with prying eyes. This is a foreboding moment of what’s to come, with Campion’s film effectively conveying the familiar terror and hyper-exposure women face for simply existing next to men, even those who have sworn to protect and serve.

While In the Cut’s central romance — refreshingly prioritising female pleasure — doesn’t question heteronormativity, Lana and Lily Wachowskis’ directorial debut Bound rejects the straightness of most noir in favour of queer love. Jennifer Tilly’s Violet is undoubtedly a femme fatale, yet she only has eyes for Corky (Gina Gershon), a butch-coded lesbian working in her building. Knee-deep in the local mafia via her money laundering boyfriend Caesar (Joe Pantoliano), Violet knows her queerness is subversive in this toxic, male environment.

Steering away from the unbalanced dynamic between men and women in noir, Bound presents Violet and Corky as equals. The film gradually builds a bridge between the two women, whose secret bond blossoms through longing stares and beautifully choreographed intimate sequences. (The Wachowskis brought sex educator Susie Bright on board for these.)

Sight takes centre stage in this neo-noir, too. After their first time together, a sated Corky whispers, “I can see again.” In the second act, Violet rushes past Corky’s hideout, manhandled by an unhinged Caesar. It’s a split-second scene: Violet silently glances at the peephole, trusting Corky would be on the other side.

Regaining a stripped-away agency doesn’t always guarantee a happy ending, though. Whether it’s Variety’s casual street harassment or In the Cut’s graphic killings, the threat of violence against women looms large in these movies. Some of the great noir stories of the past didn’t steer clear of gender-based cruelty, either. They were just too focused on male heroes — at times more fatale than any femme could ever be — to investigate the roots of these women’s subjugation.

The strictly gender-coded visual and power relations may have shifted since, yet the risks of inhabiting the world as a woman are still very visible in neo-noir, mirroring the macro and micro-aggressions of real life.

Disputing the very definition of femme fatale, neo-noir has spawned more relatable, rawer, funnier depictions of womanhood and sexuality. These female and gender-nonconforming characters defiantly inhabit their bodies and disrupt traditionally male spaces and roles. These protagonists thrive despite systemic male violence, hinting at a conversation about ‘Yes All Men’ some are still reluctant to have.

The post Women look back: celebrating the advent of the modern neo-noir appeared first on Little White Lies.

from Little White Lies https://ift.tt/oh1JbxM

via IFTTT

0 Comments