When we think of music in horror there are plenty of touchstones; stabs of strings, ominously building drones, sing-song voices and maniacal laughter. We think of terrifying, influential scores like Psycho or even modern twists like Midsommar with its sense of unease amplified by its seemingly upbeat score. What’s harder to predict are the pre-existing musical elements that weren’t originally written for horror, never conceived to be scary, which nonetheless become unnerving cultural touchstones. Perhaps this is because often once a song is well placed in a horror film it transforms forever – the flip from harmless to terrifying can be as simple as one good scene.

Chances are if you’ve been anywhere near TikTok in the last few years, you’ll be familiar with Tiny Tim. His cover of the 1929 hit ‘Tiptoe Through The Tulips’ has become a go-to “creepy” song, soundtracking countless posts on unsolved mysteries, unexplained occurrences, ghost-hunting or even horror makeup tutorials. Interestingly it was never meant to be heard this way. The original 1929 version, made popular by jazz crooner Nick Lucas, sat atop the charts for ten weeks as nothing more than a charming love song. When Tiny Tim covered the song in 1968 on his ukulele, mimicking the sickly-sweet style of the 20s with his falsetto voice, he was admittedly seen as something of a comedic novelty, but audiences found him charming and endearing. How did the song switch from charming to terrifying?

The clear moment of shift for ‘Tiptoe Through The Tulips’ is its inclusion in a memorably chilling scene from 2010 supernatural-horror Insidious. With spirits terrorising the protagonists, a record spinning relaxing piano scratches and Tiny Tim’s spectral falsetto croon creeps in as a dancing demon appears. The song has since featured in a high-spirited murder scene in Killing Eve, and bled into real-life horror in a viral news story in 2019 in which a stranger hacked into a family’s Ring doorbell, playing the song and terrifying their eight-year-old daughter. This story seems to have been the spark that lit the TikTok fire, and another of his songs ‘Living In The Sunlight’ is also often used for creepy TikToks despite its only previous major cultural use being in an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants.

Neil Lerner, Professor of Music at Davidson College, has long-studied this kind of music use in horror and even written a book Music in the Horror Film: Listening to Fear. He says that in this context “I don’t think it’s anything specific to the music. It’s the recontextualising. And it’s usually a surprising recontextualising. A song might seem just totally random, non sequitur, or trivial. If they were singing happy birthday to you [in Insidious] it would have been creepy”. The actual song choice itself is inconsequential, but once it’s been used, it’s changed forever.

Though Insidious was particularly successful in the reframing of an old song, it’s certainly not the only film to have done so. Retro music is a common trope in modern cinema; whether it’s a dusty gramophone whirring into life as a group of teens foolishly investigate a creepy basement or an old hit crackling through the static of a car stereo, we’ve seen it a thousand times. There’s The Chordettes’ ‘Mr Sandman’ soundtracking Michael Myers’ Halloween II killing spree, the whole new meaning given to Louis Armstrong’s ‘Jeepers Creepers’ lyric “where’d you get those eyes” or the old love songs echoing round the halls of The Shining’s Overlook Hotel – songs which now are more likely to have you hiding behind the sofa than waltzing round the ballroom.

These old songs work because they recall something from the past; a once comforting memory taking on sinister meaning in a time and place it doesn’t belong. The Shining is a pioneering example of the use of pre-existing music in horror with so many readings. The clearest of these is the way the bloody history of The Overlook bleeds out of the past, dragging era-specific music along with it, manifesting itself once again in Jack Torrance’s increasingly tortured mind. Michael Myers meanwhile, much like ‘Mr Sandman’, was thought to be safely locked away in memory and the ancient Jeepers Creepers beast “The Creeper” awakes only every 23 years, bringing its theme song along with it.

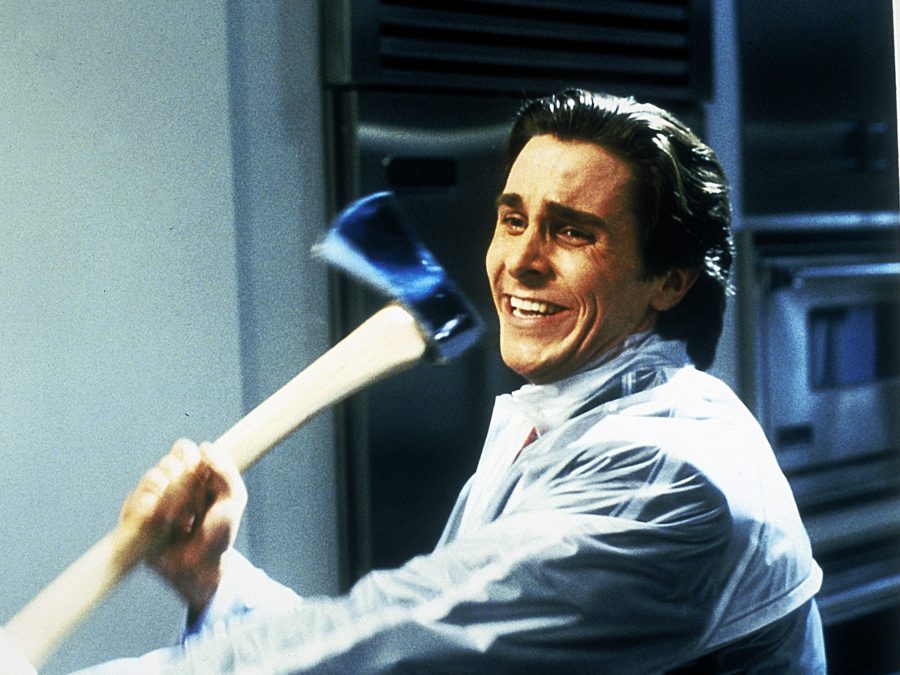

More modern songs can be just as chilling. It’s difficult to listen to Huey Lewis and the news without thinking of Patrick Bateman shuffling around in his raincoat dissecting its influence and his victim. Tom Petty’s ‘American Girl’ was once the perfect road trip song but anyone who’s seen Silence of The Lambs would be brave to play it in their car.

More recently, Jordan Peele has proven a fan of subverting once innocent songs – Us offers a striking juxtaposition from the good times of The Beach Boys ‘Good Vibrations’ against the extremely bad times taking place by the lake. Us also subverts its own uses of music. Luniz’s ‘I Got 5 On It’ goes from a song playing during a sweet family bonding moment to something more sinister through an eerie reworking later in the film. In his latest film Nope, Peele isolates the comedy lyrics of Sheb Whooley’s ‘Purple People Eater’ – a novelty song about a galactic traveler who wants to join a rock’n’roll band – and turns them into a chilling monologue delivered by gruff-voiced cinematographer Antlers Holst (played by the impeccable Michael Wincott).

The use of modern songs in horror often has quite the opposite effect of older songs; they seem terrifying simply because they are so commonplace. “What the scholars would call that,” Lerner says, “is ‘anempathy’. An anempathetic musical cue would mean that the music is not matching what we think we’re seeing on screen, it’s somehow cutting against the grain of that.” There’s nothing scarier than scenes in horror films that could easily happen to you. It’s often cheerier, non-threatening songs that work since that’s where you feel farthest from grisly consequences.

We’ve all been back to somebody’s house only for them to go on and on about the song on the stereo, but the thought that an excruciating rant about Huey Lewis could go from boring to deadly is what makes American Psycho resonate. There’s nothing better than driving to your favourite song or dancing on your holiday, but the idea that when your guard is down could be when you’re at your most vulnerable is enough to make you drive in silence. As for ‘Purple People Eater’ – that shattering of childlike innocence and safety is a horror tool as old as the genre itself, with countless nursery rhymes tainted forever by the creepy kids in horror films.

Neil Lerner points out an interesting study he did in lectures that speaks to this. Taking the shower scene from Psycho – featuring one of the most iconic pieces of original horror music ever from composer Bernard Herrmann – he subbed out the audio for various choices. One of which was Celine Dion’s ‘My Heart Will Go On’, a hilariously non-threatening choice. To his surprise “it was actually the creepiest version of it. It was really horrible. Students were extremely distressed about it”. Having discussed it with them after, “they seem to think it was because with the screeching violins, at least there was a sort of separation. It’s imagination. It’s nightmare, but it’s not real. But suddenly, a song that at that time was on the radio in daily life, suddenly that brought it to close to home”.

There are also things you can infer through pre-existing music more subtly than you ever could through score or dialogue. There are often underlying politics to horror, and Jordan Peele’s films are clear examples of that. Us seems to speak to Trump’s America at the time of release with ‘Good Vibrations’ possibly a reference to the good and easy times for those on top while the “Tethered” underground are forgotten.

Whole essays have been written about ‘I Got 5 On It’ and its speculated meaning, the history that lives within the song’s many samples telling a story of appropriation and misrepresentation. Then there’s the selective nature of the Purple People Eater towards its prey; in the song, he claims he won’t eat the singer because “you’re too tough”. When used by a director whose work is so imbued with ideas around race and class, it’s possible to see this song’s inclusion as a wry nod towards Hollywood’s history of exploitation and selectivity.

More than perhaps any other film genre, music can make or break a horror movie. Effective uses of songs in slashers stay with you, creeping into your brain late at night or coming flashing back during what was once a mundane activity. While original scores are so often a huge part of what makes horror so effective, you can always escape a score – what you can’t escape though are the songs that don’t live solely within the film.

There are countless examples of songs that if you’ve seen certain films will stop you in your tracks: Mike Oldfield’s ‘Tubular Bells’ in The Exorcist; The Everly Brothers’ ‘All I Have To Do Is Dream’ in A Nightmare On Elm Street; even “a bit of the old Ludwig Van” in A Clockwork Orange, after which Beethoven will never sound quite the same. Cleverly placed music can make horror crawl out of the screen and into real life. At least you can always be safe in the knowledge that the scenes these songs are forever tied to could never happen to you…right?

The post How wholesome songs become horrifying through cinema appeared first on Little White Lies.

from Little White Lies https://ift.tt/eqEIr65

via IFTTT

0 Comments